”Eine ungewöhnliche Freundschaft – Generalmajor Rüdiger Graf von der Goltz und

Juho Kusti Paasikivi”

An unsual friendship – Major General Rüdiger von der Goltz and Juho Kusti Paasikivi

The German intervention in the Finnish Civil War in spring 1918 was led by Major General von der Goltz. He became close friends with Paasikivi, who had been made Prime Minister in May, and his family. The friendship continued after the German troops left Finland in December 1918. In this article, Professor Dörte Putensen discusses and analyses this unusual friendship.

Major-General Count Rüdiger von der Goltz came from a large, old noble family, and had a long and successful military career behind him when, in late February 1918, he was informed of a planned deployment in Finland, bringing him into contact with Finland for the first time in his life.

His contemporaries and peers considered him to be a man with “exceptional drive and determination”; he was also known as, and considered himself to be, a clear “scourge and hater of Bolsheviks.” (1) His nine-month deployment in Finland, heading the Baltic Sea Division from April to December 1918, actually only accounted for a small proportion of his entire military career. However, this left such a deep mark on him that he felt a connection with Finland until he died. In February 1918, he received the order to head the Baltic Sea Division to provide military support to the Whites in the Finnish Civil War against the Reds, who controlled the south of the country. Initially, he assumed that this was a military demotion, but later he would see his deployment in Finland as the high point of his military and political career.

There was interest in the intervention both on the German and the Finnish side.

To hide the fact that they were clearly taking sides in the civil war, the agreed formulation was that the aim of the German troops was not to interfere in the internal conflicts of the Finns, but rather to offer assistance in the fight against outside gangs.(2) Mannerheim, who had initially rejected the German intervention, also agreed with this formulation. Ultimately, he agreed to it under the condition that the German troops were placed under his command. There was no objection to this from the German side. However, this demand proved to be ineffective, as von der Goltz did not want to place himself under Mannerheim’s command. Rather, he wanted at least to take Helsinki under his leadership. So, on 10th May, the first meeting was held between von der Goltz and Mannerheim. Their relationship was tense, and remained so.(3)

Despite evidence to the contrary, von der Goltz always maintained that he had no desire to interfere in Finnish internal politics, justifying the military intervention as a non-partisan, humanitarian “police measure” against “murderous and thieving rabble”.

From the perspective of Finnish civil society, Germany’s intervention was valued as an “incomparable cultural asset”. The head of the German supreme command, Ludendorff, made it clear in his memoires, written in 1919, that despite Finnish professions of sympathy, it was not Finnish but rather solely German interests that brought German troops to Finland. (4) However, the myth of disinterested German liberators led by Rüdiger von der Goltz in Finland persisted at least until the Second World War.

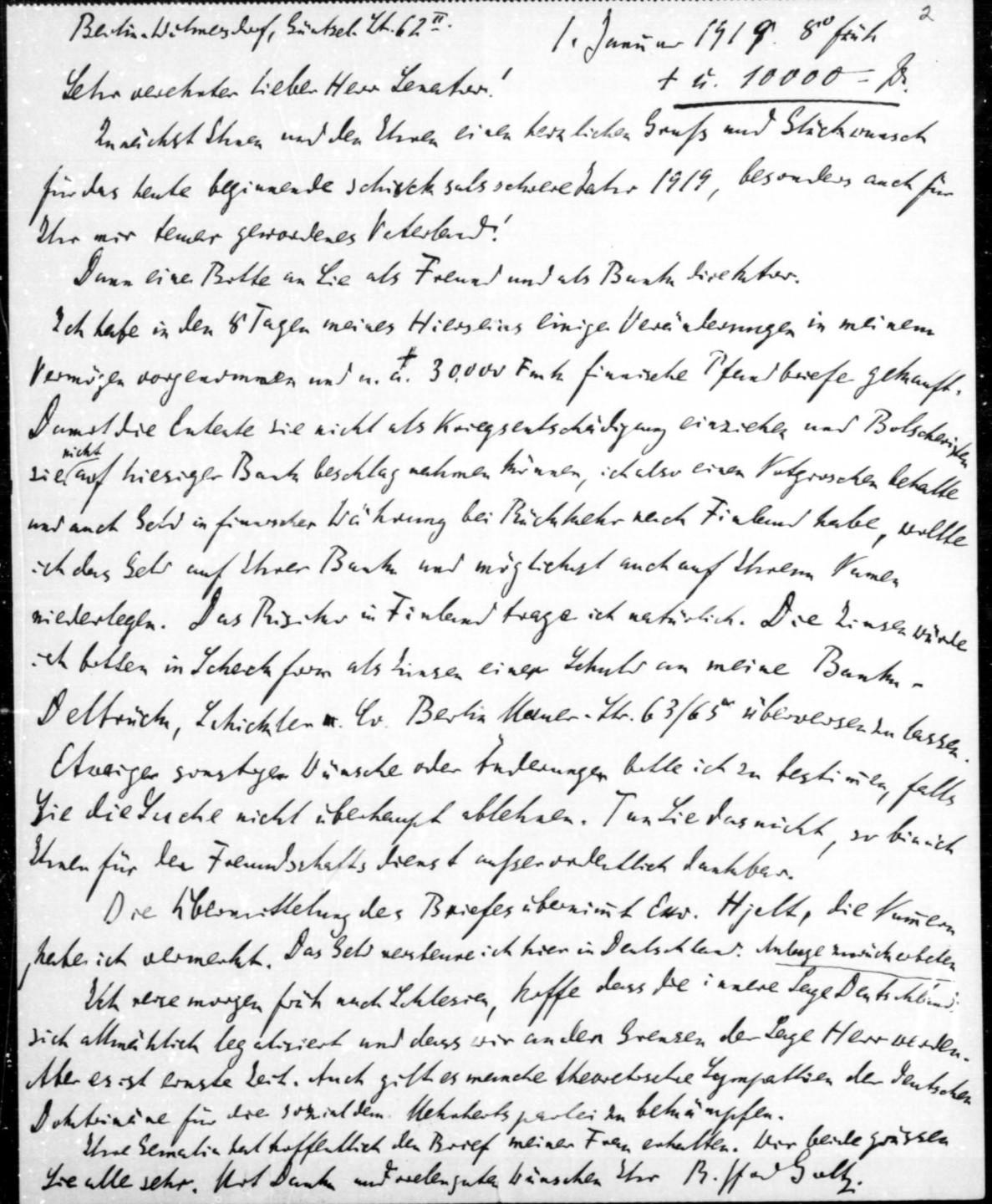

Fig. 1: Letter from Rüdiger von der Goltz to Juho Kusti Paasikivi, dated 1/1/1919.

For von der Goltz, the great significance of his deployment in Finland stemmed not just from the rapid military success, but also from the fact that after the civil war, he remained in Finland with the Baltic Sea Division. Imperial regent P.E. Svinhufvud and the government under J. K. Paasikivi considered that Germany’s protection was still necessary after the end of the civil war for various reasons.

At the request of the Finnish government, and on the orders of the German supreme command, von der Goltz received the order to build up Finnish armed forces in the Prussian mould, and to place them under a de facto German command. This was an uncommon and unusual task for an officer, but certainly a very lucrative one. Along with Svindhufvud and Paasikivi, he was one of the most powerful people in Finland until the end of 1918. Until December 1918, he was acting as the “German general in Finland”. This was a title granted to him by Kaiser Wilhelm II in July 1918, which further elevated his status. He led the structuring of the Finnish army in the German mould (5) and as a self-styled “political general”, he was the most important representative and advocate of the incorporation of Finland in the German sphere of influence.

Von der Goltz worked tirelessly among Finnish monarchists to ensure the election of a German prince, if possible a son of Wilhelm II, as King of Finland, as the surest guarantee of integrating Finland permanently in Germany’s dominion.

Imperial Germany’s defeat in the First World War in November 1918 brought the Finnish public’s steadfast focus on Germany to an abrupt end; what remained was gratitude among broad sections of Finnish society to the German “liberators”.

The withdrawal of the last Germans necessarily led to a political reorientation in Finland. On 27th November, the senate, led by Paasikivi, resigned, and on 12th December Svinhufvud stepped down as imperial regent. Two days later, Friedrich Karl von Hessen renounced the Finnish throne. Mannerheim became imperial regent.

The issue of the monarchy had to be shelved. Then, in July 1919, after long, vigorous discussions, the republic was the form of government established in the constitution. One of its key characteristics – partly as a concession to advocates of a monarchy – was the strong position of the president. The new Finnish governments were oriented towards the winning powers, England and France.

There were also changes in the party structure. Those sections of society that still longed for a monarchy came together in the conservative National Coalition. Many of their leaders and members deeply regretted the departure of the Germans, continuing to believe in their liberating mission, and did not break contact with Rüdiger von der Goltz. Their main representatives were the senate members of 1918, especially P.E. Svinhufvud and J.K. Paasikivi. The republican, west-oriented portion of the population, including Mannerheim, was relieved to see the departure of the German troops. These forces came together to form the National Progressive Party. Von der Goltz quickly became established in Finland, for understandable reasons. This was due to his swift military successes and the powerful position he later gained, as well as the effusive honouring of the “liberator”, not just by most leading White politicians, but also by the country’s entire elite, and other sectors of the population, who gave von der Goltz’s soldiers an open and friendly welcome, fêting them as “rescuers”, with expressed gratitude for decades. Thus Finland became a sort of “second home” for von der Goltz and his wife.

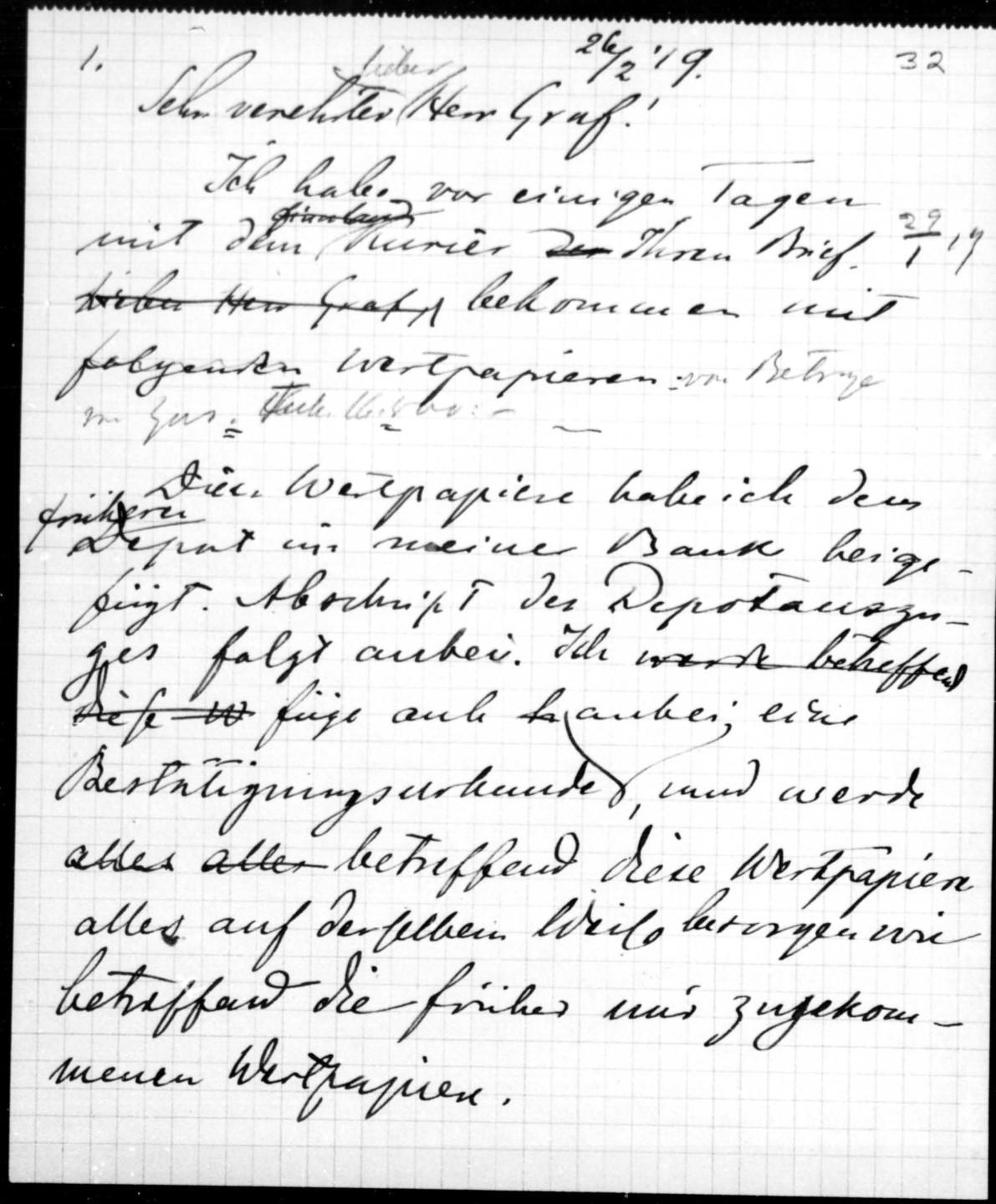

Fig. 2: Extract from a draft letter from Juho Kusti Paasikivi to

Rüdiger von der Goltz, dated 26/2/1919.

Rüdiger von der Goltz’s experiences in Finland were so significant and lasting that he remained an imperial officer in his thinking and actions for the rest of his life, open in his opposition to the Weimar Republic, and rejecting parliamentarianism and democracy. He actively strengthened the Völkisch movement and associated forces in Germany, and as he agreed at least partly with Hitler’s goals, he became an active proponent of National Socialism, although towards the end of the 1930s he tended to adopt a more sober approach, distancing himself from the Nazi leaders.

As generals in his homeland occupied an increasingly marginal position, accustomed as they were to success and power, von der Goltz enjoyed the honour and gratitude of Finnish society all the more. He carried out many activities to ensure that contact with Finland was not lost, and he worked to shape the image of Finland in Germany, and the image of Germany in Finland, and to keep the memory of his “Finnish mission” alive. Von der Goltz wrote memoires, did publicity work, founded and directed a “German-Finnish Society of 1918”, headed various delegations to Finland as a celebrated war hero and liberator in 1923, 1928, 1933, and 1938 on the anniversary of the taking of Helsinki, and he spared no effort in maintaining many of his professional and personal contacts from 1918 – through correspondence or through personal meetings.

The closest and most lasting contact was between Rüdiger von der Goltz and J.K. Paasikivi. They were joined by the memories of their time together during the dramatic events of 1918. They held each other in high esteem, and their good relations benefited them both in different ways.

Paasikivi, apart from his political effectiveness, was the Chief General Manager of the largest private bank in Finland, the Kansallis-Osake-Pankki (KOP). He had professional relations with German bankers between the wars, but he had no direct contact with German politicians and little first-hand knowledge of circumstances in Germany. This meant that contact with von der Goltz was valuable for him.

After the Second World War, he described Rüdiger von der Goltz as a “reasonable and clear German patriot”, who also loved Finland, and said that “as a Prussian solder he was less rigid and biased in his opinions that I had imagined”. Paasikivi particularly valued von der Goltz’s loyalty and, surprisingly, also his non-intervention in Finnish internal affairs. (6)

Von der Goltz, in turn, praised Paasikivi as a “clever, statesmanlike person, a well-respected character and lovable person, with whose family I formed close bonds of friendship.” (7)

These “bonds of friendship” were reflected in regular contact and an intense exchange of ideas over more than two decades – mutual visits in Berlin and Helsinki, shared spa visits, and intensive correspondence.

Fig. 3: The Goltz family and Paasikivi by the Baltic Sea, 1923:

Anna Paasikivi with the oldest grandchildren of Rüdiger and Hannah

von der Goltz, J. K. Paasikivi, Rüdiger von der Goltz with his wife Hannah, his daughter-in-law Astrid, with her daughter Astrid and son Rüdiger

(left to right; property of the family).

Unfortunately not all the letters have been preserved. While 75 letters and postcards from von der Goltz remain, only a few draft letters from Paasikivi are still in existence.

The imbalance in the correspondence that is still available does not imply that von der Goltz was more enthusiastic in his exchange with Paasikivi, but is rather due to the fact that only those letters from von der Goltz are preserved and accessible in the National Archive in Helsinki. Von der Goltz’s thanks and references to letters received from Paasikivi imply that both sides were equally active in their correspondence. Letters from Paasikivi to Rüdiger von der Goltz were probably lost during the Second World War, when the Goltz house in Berlin-Charlottenburg, at Kurlandallee 38, was destroyed in December 1943 during one of the largest air attacks on Berlin. (8)

As well as personal and family information, and perspectives on political developments in Finland, Russia, and Germany, half of all the letters make reference to financial transactions that Paasikivi carried out for Rüdiger von der Goltz.

Immediately after his return from Finland, von der Goltz informed Paasikivi that he had made changes to his assets and acquired bonds for 30,000 FIM. Upon informing him of this, von der Goltz asked for an account to be opened at the bank run by Paasikivi – if possible under the name Paasikivi – so that his assets would be safe from the Entente and the Bolsheviks, and he would have some emergency funds upon his return to Finland. (9)

In fact, in the years to follow, von der Goltz toyed repeatedly with the idea of moving to Finland if conditions in Germany became untenable for him. Paasikivi was prepared to do this good turn, and he handled the matter immediately at his bank by depositing von der Goltz’s money at the KOP in his own name. It was also agreed at the same time that the interest upon maturity would be paid to the banking house of Delbrück Schickler & Co. Berlin, into the account of the spouse of the Count von der Goltz. This settled basic matters, and other financial transactions could be handled. (10)

In Finland, a women’s committee headed by Paasikivi’s wife, Anna, started a collection for Rüdiger von der Goltz, a “tribute” as they called it – to express gratitude for his deployment in the Finnish Civil war, and to recognise his complicated financial situation after he left the army. The list of donors who had made a donation of at least 300 Finnish marks included about a thousand names, although this was not published for domestic political reasons. This “tribute”, worth 361,000 Finnish marks, which at the exchange rate in 1920 was worth more than a million Reichsmarks, was presented to the General symbolically in June 1920. Rüdiger von der Goltz was given full right of disposition, so he could decide where and how the money should be invested. He instructed that half of this money should be given to his sons. Of the amount remaining, half was deposited in Finland in the account opened for him at KOP by Paasikivi.

Both Paasikivi and von der Goltz thought it was advantageous to invest money in Finland, as conditions were calmer and more secure than in Germany, and this ultimately proved to be correct, as, in this way, the money was saved from inflation. For a long time, Paasikivi also ensured that the invested capital grew through earnings from interest and securities transactions.

It is difficult to determine whether these transactions entirely complied with official rules. Paasikivi certainly had some leeway as the bank director, and knew how to use it. In any case, they were advantageous for Rüdiger von der Goltz in many ways. He was certainly aware of this. In 1926, he admitted to Paasikivi that he had mainly been living on the tribute for four years, and he had used it to build his house, while his pension was largely devalued by the time he received it. (11)

In virtually every letter, von der Goltz told Paasikivi about his family situation, his health (illnesses), and that of his family members; understandably, with age, these sections became longer and more detailed. As both couples went on long spa trips or holidays every year, they exchanged experiences about individual places or facilities, and they tried to coordinate these trips to visit each other. The two couples preferred to stay in first-class spa resorts in Bavaria, Italy, Switzerland, or Austria. Their letters often discussed the development of von der Goltz’s sons, and his final total of 15 grandchildren. Like Paasikivi’s children, they were included in the friendly contact. (12) The warm relations between the two fathers led over time to a family friendship. Both sons met repeatedly with Paasikivi, his wife and family – during their visits to Berlin or during their stays in Finland, mostly accompanying their father (1923, 1928, and 1938).

Rüdiger von der Goltz and his wife Hannah, for their part, took an active interest in events in the Paasikivi family, and they were deeply moved and full of sympathy upon the death of Paasikivi’s first wife and his two sons.

A third issue that featured prominently in the letters was political problems. Despite their differences, the political views of von der Goltz and Paasikivi also showed many similarities. In 1918, they were both monarchists. Von der Goltz remained so until the end of his life, while Paasikivi took a republican position after the fall of the monarchy in Germany, although initially he did not entirely give up hope of a possible monarchy, and he probably retained a certain inner monarchist bent until the end of his life.

Both von der Goltz and Paasikivi were unsettled by the many changes of government in the 1920s, both in Finland and Germany. Paasikivi saw these changes as a sign of the delicate and fragile circumstances after the civil war, and advocated strong governments, excluding the Social Democrats. Rüdiger von der Goltz, however, saw the frequent changes of government in Germany as a “cancer of democracy”.

Fig. 4: Rüdiger von der Goltz arriving at the port of Helsinki for celebrations of the 15th anniversary of the taking of Helsinki by German troops.

Unlike von der Goltz, Paasikivi regarded the republic and parliamentary democracy with some scepticism, but did not go so far as to entirely reject it like von der Goltz.

In relation to developments in Germany, it was clear that Paasikivi largely shared the critical opinion of his correspondent. Paasikivi also viewed Germany with concern in the 1920s, although he was also critical of political developments in Finland. Von der Goltz did not entirely contradict this evaluation, although he tended to idealise the political situation in Finland as a whole. In the 1930s, von der Goltz made no secret to Paasikivi of the fact that he supported the Hitler regime. He defended Hitler’s policies as necessary steps towards the reconstruction of Germany’s former greatness, and he ignored the danger that this regime would start a war. Paasikivi had observed Rüdiger von der Goltz’s support for Hitler’s dictatorship, but as far as we know, he did not contradict von der Goltz.

Although the correspondence with Paasikivi does not shed light on Rüdiger von der Goltz’s feelings at the start of the Second World War, von der Goltz clearly expressed his sympathy for Finland’s predicament during the Winter War between the Soviet Union and Finland. He followed events in and around Finland closely, he was proud of the Finnish armed forces’ bitter resistance, and he hoped that his deployment in 1918 had not been in vain. He criticised German restraint in relation to Finland, and he repeatedly showed open support for Finland. Paasikivi expressed openly to Rüdiger von der Goltz his disappointment with Germany’s position, and in full knowledge that his friend was now a civilian, Paasikivi asked him to relay his position “through any channels”, and to support the idea of Germany pushing for “Soviet Russia to return to the negotiating table with us.” (13) Rüdiger von der Goltz was very understanding of Paasikivi’s request, and in several letters he gave the advice of “a private citizen who reads the newspapers”, but despite his sympathy for Finland, he asked for understanding for Germany’s restraint. Paasikivi took Rüdiger von der Goltz’s suggestions very seriously, as in his opinion, they were more than the interpretations of a civilian. Paasikivi was convinced that von der Goltz had passed his request on to Hitler, and that von der Goltz’s answer was the official German position. (14)

Von der Goltz was enthusiastic about the “new” brotherhood of arms between Germany and Finland from mid-1941.

Even though Rüdiger von der Goltz began to criticise the way Hitler was fighting the war unofficially in family circles as early as 1940, in early 1942, he still told Paasikivi that Germany was militarily, economically, and therefore also politically unbeatable. A year later, in the last letter that is preserved, his analysis sounded rather more sceptical, although he was still sure of victory. His disappointment and desperation was all the greater when the war ended. He thought that the Potsdam Agreement was a “step back into a Slavic lack of culture”. On 4th November 1946, von der Goltz died at Gut Kinsegg in Bernbeuren, from the effects of a stroke.

Dörte Putensen, born 1949, Studied Northern European Studies at Greifswald, 1976 Doctorate, 1985 Docent, 2003 Adjunct Professor in Rostock. Subject areas: General contemporary history, Nordic history. Research focuses: History of the Nordic labour movement, German-Finnish relations.

This is a translation of the original text in German “Eine ungewöhnliche Freundschaft”, which is also published on this site. Translation is made by AAC Global Oy.

Sources

1. Hans Möller-Witten, Ein preußisches Soldatengeschlecht, Barch N 714/14

2. See: Marjaliisa Hentilä, Seppo Hentilä, 1918 Das deutsche Finnland. Die Rolle der Deutschen im finnischen Bürgerkrieg, Regensburg, 2018, p. 83 et seq.

3. See Touko Perko, Haastaja Saksasta 1918 von der Goltz ja Mannerheim, Jyväskylä, 2018, p. 84

4. Erich Ludendorff, Meine Kriegserinnerungen 1914-1918, Berlin, 1919, p. 506.

5. See: Manfred Menger, Die Finnlandpolitik des deutschen Imperialismus 1917-1918, Berlin, 1974, p. 211

6. T. Polvinen, H.Heikkilä, H.Immonen, J.K. Paasikivi Valtiomiehen elämäntyö 1870–1918, WSOY, 1989, p. 427.

7. Rüdiger von der Goltz, Meine Sendung in Finnland und im Baltikum, Leipzig, 1920, p. 85.

8. See: Hans Gerlach, Nachrichten über die Familie der Grafen und Freiherren v. d. Goltz 1885-1960, Neustadt an der Aisch, 1960. p. 192.

9. See appendix, Kansallisarkisto (KA), J. K. Paasikiven arkisto, Kirjeet ja kirjekonseptit, Kotelo I:3, p.1, Letter from Rüdiger von der Goltz to Juho Kusti Paasikivik dated 1/1/1919

10. See appendix, ibid., p. 32 Extract from correspondence from J. K. Paasikivi to Rüdiger von der Goltz, dated 26/2/1919

11. Ibid., pp. 132-135, Goltz to Paasikivi, dated 10/3/1926.

12. See appendix: Picture of the Goltz family and Paasikivi by the Baltic Sea, 1923

13. KA, J. K. Paasikiven arkisto, Toimintani Moskovassa ja Suomessa, Talvisodan aika Kotelo VI:34, J. K. Paasikivi to von der Goltz, dated 5/1/1940

14. J. K. Paasikivi, Meine Moskauer Mission 1939-41, Hamburg, 1964, p. 157

2. Saksan apu Suomelle (German aid to Finland)