Paasikivi’s main focus during the three years as the Finnish ambassador in Stockholm was Finland’s security. Convincing Sweden to cooperate and support Finland’s independence was crucial. Moreover, the dispute over the Åland Islands also remained unresolved. Paasikivi believed that cooperation between Finland and Sweden would also improve relations with the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union, however, saw things differently.

Taking the post of the ambassador in Stockholm in autumn 1936 was not an easy decision for Paasikivi. The National Coalition Party wanted to keep their leader in Finland and diplomacy was not appealing to Paasikivi. The rethinking of its position in relation to foreign powers that took place 1935 saw Finland turn from its border state policy towards Nordic cooperation and seeking closer relations with its western neighbour. The new direction in foreign policy was authored by Svinhufvud, Kivimäki and Hackzell. Paasikivi as well as Mannerheim had both contributed this development. Within the Nordic context, the relationship with Sweden was crucially important. Paasikivi thought Sweden was a far more significant country than its size or population would have one believe. And the best place to influence Sweden’s foreign policy was in Stockholm. Paasikivi, a Fennoman in thought, word, and deed, eventually yielded under the pressure from the president and prime minister and presented his letter of credence to King Gustaf V in Stockholm in December 1936.

Paasikivi’s appointment was an exception to the well-established rule that ambassadors came from the ranks of career civil servants. After the idyllic 1920s, the 1930s was a decade of mounting problems, including in the foreign administration. As the military and political tensions in Europe peaked, the workload and duties in the foreign service changed and multiplied. At the time when Paasikivi took office as ambassador, the embassy was undergoing a very hectic period. The entire embassy staff worked hard and long hours. The contacts between the Ministry for Foreign Affairs and the Stockholm Embassy, as well as the relations with the Swedish Government managed from Stockholm, were a lifeline in terms of Finland’s foreign relations and security.

Det hotade och det skyddade landet – the threatened and the protected

Paasikivi’s main focus of attention in Stockholm would always be security. The heading of his first report was tellingly “The defence question in the Nordic countries”. Europe was spiralling towards hostilities and the pressure from the Soviet Union was heavily felt in Finland. The situational analysis arrived at by both Stockholm and Helsinki – the country that was protected and its neighbour that was under threat – was largely similar, but there were certain differences, too. The differences were due to the difference in the two countries’ geopolitical situation. Sweden felt that its military and political position was strong. Finland, on the other hand, had to seriously consider the possibility of being a target of direct invasion. In Paasikivi’s view, Sweden was the only country in whose own national interest it was to defend Finland’s independence. Sweden would also be the only country through which Finland could obtain material assistance if at war. Therefore, bringing Sweden in line to support Finland was paramount. This was also Mannerheim’s opinion. Nordic cooperation was the way in which Finland should proceed without hesitation, without looking back.

However, there were obstacles in the way. The atrocities committed during the Finnish Civil War, the Lapua movement and right-wing radicalism, the language question and the border states policy raised questions among Swedish politicians. Independent Finland had swung to the right, while Sweden was heading towards the left. The League of Nations resolution on the Åland Islands and the Greater Finland aspirations were a burden on the relations. The assurance of Kivimäki’s government of Finland’s political neutrality and Nordic alignment calmed minds, but any hopes for a defence alliance were not reciprocated. The status of the Swedish language as Finland’s second language raised doubts among the Swedes. Paasikivi spoke to Tanner about his frustration over the inability of his countrymen to see the significance of the Swedish language to Finland’s foreign relations.

Paasikivi described the sentiments of the Swedes before the war in his report of February 1937: “I believe that for a great majority of the Swedes, Finland’s independence is all well and good, but not vital.” A year later, he reiterated his observations: “There are circles in Sweden who do not consider Finland’s independence to be a matter of vital significance for Sweden.” The “Finnish cause” was mainly taken up by the royalist Swedes. The socially democratic Sweden saw thigs differently. Tage Erlander explained to a fellow social democrat why Sweden should not be part of Finland’s defence: “If you could form a real analysis of the sentiments of the Swedish people towards Finland, you would be surprised. War on Finland’s behalf would be a most unpopular endeavour. There are deep misgivings among people towards the Finns.” Erlander was a social democrat who belonged to anglophile intellectual circles with a much greater interest in countries south of Sweden and in Denmark than in Finland. At the same time, there was strong aversion to Germany. There was no clear agreement on who the enemy was. The communists in Sweden and the influential Soviet ambassador Alexandra Kollontai drove a wedge between the Finnish and Swedish views on defence cooperation. Kollontai did not keep close contact with her Finnish counterpart, and there are hardly any references in Paasikivi’s diaries on his relationship with Kollontai.

In his reports, Paasikivi stated that Sweden was a democratic country “where it is not possible to pursue policies that do not have popular support.” Staying neutral in a possible conflict between great powers was the prevailing stance of the majority. Sweden the “Folkhemmet”, people’s home, was building a welfare state, and this along with internal security took priority over foreign policy. Reaching consensus on a policy in favour of a military intervention in Finland was difficult. The attitude of the Swedes came as no surprise to pragmatic politicians such as Mannerheim and Paasikivi, but irked many leading Finnish politicians, diplomats, and officers. The assistance given by Sweden to Finland against the Soviet Union was emphatically one-sided and went against the idea of a mutual defence alliance. As Max Jacobson has pointed out, the thought of giving Sweden military assistance never even crossed anyone’s mind in Finland.

The Åland Islands

The power balance on the Baltic Sea was shifting. From the spring of 1938 onwards, Paasikivi focused his energies on the issues surrounding the Åland Islands question. This was one area where the neighbours agreed on the common threat, and the islands should not be left in a military void. It was important for Sweden that the Åland Islands – a gun aimed at the heart of Sweden – was not occupied by a hostile great power. By this, the Swedes referred primarily to Germany, and the Finns to the Soviet Union. Building fortifications on the islands was crucial and would underpin security cooperation between Finland and Sweden. Paasikivi saw that this would eventually lead to a deeper military alliance.

After intense negotiations, an agreement on the fortification of the Åland Islands was reached in January 1939. Going forward with the plan, however, depended on the approval from the countries who had signed the international treaty on the Åland Islands. Sweden also wanted to consult the Soviet Union. Paasikivi considered this practically a veto handed to the Soviet Union, which it would not hesitate to use. This was to be the case, and in June, the Swedish government postponed any decision on the plan. The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact signed in August was decisive for Sweden. In the light of the Pact, participating in the defence of the Åland Islands could be perceived as an action against the Soviet Union. If Stalin had been given free rein in Finland, it was fair to assume that Hitler had taken similar liberties in pressuring Sweden. Kollontai explained to Swedish leaders that Germany was behind the militarisation of the Åland Islands. Germany wanted to establish a military base on the Baltic Sea.

After Finland received Moscow’s ultimatum in October 1939, Sweden took the final decision to step back. Prime Minister Hansson wrote to Tanner that Finland could not expect Sweden to act upon the previous plans regarding the Åland Islands, let alone those on any military intervention in Finland. However, the circles that were favourable towards Finland gave a different impression of Sweden’s reactions in the event of an invasion in Finland. Finnish leaders had difficulties trying to ascertain what Sweden’s final position was. There was still some hope, and as late as in August 1939 Paasikivi reported optimistically about the plan for the Åland Islands. He was concerned about the change in the foreign policy thinking in Finland. “An excessive sense of power and overestimating our strength is pure fantasy and free from reality.” He was also apprehensive about the difficulties that were mounting in the way of good relations with the Soviet Union. Russia and Sweden were the two countries upon which the existence of Finland depended, as Paasikivi stated. Paasikivi, whose aim was to improve Finland’s relations with the Soviet Union on the basis of cooperation with Sweden, could not understand why the Soviet Union should oppose this cooperation. He believed that the Soviet Union would not start a war against Finland if Sweden committed to ally itself with Finland. Sweden, however, was neither ready nor willing to do so.

“Finlands sak är vår” – Finland’s cause is ours

On 5 October 1939, Finland received an invitation from Moscow to attend negotiations on “concrete political questions”. The same evening, Paasikivi was urgently called back to Finland. He flew to Helsinki on the same day, and left Stockholm never to return as an ambassador. Paasikivi, who was familiar with the Russian mentality and had experience in negotiating with the Russians, was appointed to head the Finnish delegation.

Paasikivi’s efforts in Sweden remained unfinished. The Åland Islands were not fortified and the hopes for military cooperation were unfulfilled. The Winter War began, and the feelings among Finns were bitter. Many felt that Sweden had betrayed Finland.

Towards the end of the Winter War, Paasikivi asked President Kallio whether he had received any response from Sweden while in Stockholm in October regarding military assistance to Finland. According to Kallio, they had never asked the question, as they feared that the response would be negative. It has since been concluded in critical historical inquiry that Finland’s expectations were simply excessive. Sweden’s evasive conduct was misinterpreted in Finland. Sweden never violated any agreement with Finland, as no such agreement existed. Finland held hopes that were unfounded. The misconception was also upheld by the prominent campaign of the friends of Finland, who were in support of Sweden offering military backing to Finland.

The fact that Sweden had declared itself “non-belligerent”, rather than neutral, meant that it could offer aid to Finland. While there were no Swedish divisions fighting in the Winter War, the amount of assistance was considerable. The monetary value of the support has been estimates at EUR 120 million. More than 9,000 Swedish volunteers fought in the Winter War. The weapons, ammunition, vehicles, and aircraft (142 in total) were a critical addition to the resources of a country engaging in a defence action against a much greater power. Sweden also offered refuge to 12,000 children, mothers, and old people, which alleviated the humanitarian emergency in Finland.

Krister Wahlbäck, a Swedish historian, has provided an accurate description of the sentiments on both sides of the Gulf of Bothnia: “If Finland felt that she had been betrayed and sacrificed, Sweden had every reason to feel misunderstood and depreciated.”

During the Continuation War, Paasikivi returned to Stockholm on several occasions. On these visits, he was met with similar attitudes familiar from the time of the Winter War. The writing was on the wall: we cannot change geography. Acknowledging reality is the beginning of all wisdom.

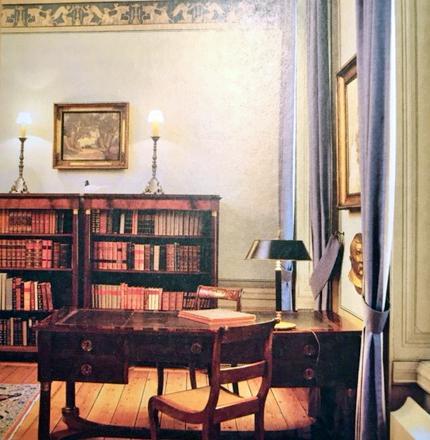

Pertti Torstila is a former diplomat, whose final ambassadorial posting in his 44-year-long career in the foreign service was in Stockholm in 2002–2006. Paasikivi’s desk, pictured, is the same desk which Torstila also wrote his ambassador’s reports from.

Sources

1. Tage Erlander: 1901−1939. Tidens förlag, 1972.

2. Toivo Heikkilä: Paasikivi peräsimessä: pääministerin sihteerin muistelmat 1944−1948. Patexpert, 1991.

3. Max Jakobson: Paasikivi Tukholmassa: J. K. Paasikiven toiminta Suomen lähettiläänä Tukholmassa 1936−39.

Otava, 1978.

4 Tuomo Polvinen, Hannu Heikkilä & Hannu Immonen: J.K. Paasikivi: valtiomiehen elämäntyö 2, 1918−1939.

WSOY, 1992.

5. Krister Wahlbäck: Jättens andedräkt. Finlandsfrågan i svensk politik 1809−2009. Atlantis, 2011.

Translation: AAC Global 2020