It was a widely held interpretation in Finland in the post-war period that the Soviet Union controlled the security environment around the Baltic and the Arctic Sea with such overwhelming supremacy that there was no other alternative than to concede all her demands. President J. K. Paasikivi was a determined leader of this policy, and he silenced any opposition with his scathing argumentation.

Behind closed doors, however, he would lament the difficulty of his official role and the impertinence of the Soviet Union. This side to his character did not reach public awareness until decades later when his diaries were published. His diaries as well as archival sources have since revealed that while Paasikivi was preaching friendship with the Soviet Union, behind the scenes he was turning to the West for support. Initially this was with small, tentative, and mainly symbolic steps, but such as they were, they appeared to alleviate Paasikivi’s anguish.

Cautious beginning

In a conversation with Maxwell Hamilton, the US Ambassador to Finland, in September 1946, Paasikivi explained Finland’s membership applications to the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development IRB and the International Monetary Fund IMF. He made no bones about the political, historical, and philosophical motivation behind the choice: “We are one of the Nordic Countries. Our history, our governmental, economic, and social structures are Nordic, mainly Swedish. […]We want to overcome our difficulties without losing our freedom. This is why we are turning towards the West for assistance. We do not wish to rely on the East.”

A week prior to his meeting with the ambassador, Paasikivi had rejected the offer made by the Soviet Union to acquire major stakes in Finland’s key industrial companies. Paasikivi stated that he considered the proposal an intervention in Finland’s internal affairs. Having to fend off such a hostile gesture from the Soviet Union, he turned to the United States for support.

To ensure that his message would be understood by Western powers, he also communicated it to London. In March 1947, Paasikivi related to Francis Shepherd, the British Political Representative in Finland, that Finland was identifying with the West because Russia represented a foreign world. Paasikivi admitted that it was in the Russian interest to stop Finland from becoming a base for an attack against the Soviet Union and that he fully understood the Soviet position in this regard. Christopher Warner, Head of the Northern Affairs at the British Foreign Office, wrote in the margins of the report that described this conversation: “Mr. Paasikivi is a wise man.”

Distancing from the East

Paasikivi had already accumulated a wealth of experience from the decades preceding the Second World War on the political culture of the Soviet Russia and the Soviet Union. He had been a member of the Finnish delegation at the Tartu peace negotiations in the early 1920s and, more importantly, he had represented Finland as a negotiating party and an envoy in Moscow in the months preceding and following the Winter War in 1940.

At that point, Paasikivi had endured a series of late-night confrontations, one more chaotic than the other, with the Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov. He would habitually be summoned at a moment’s notice and without the support of his government in Helsinki to protect Finland’s interests in relentless intellectual battles with a hostile counterpart.

Under the pressure of these desperate duels that Paasikivi fought in the Kremlin in the autumn following the Winter War, he appears to have experienced a type of light-at-the-end-of-the-tunnel epiphany as the talks in Stockholm on a potential union between Sweden and Finland seemed to be bringing results. Paasikivi advised President Risto Ryti to hold on to Sweden for dear life, even if they were unlikely to provide any more assistance than they had during the Winter War.

It would seem that Paasikivi was expecting a major change in the relations and he was excited by this turn of events. Finland attempted to associate itself with the Scandinavian West while distancing itself from the Eastern sphere and Russia. The enthusiastic message that he sent to Ryti 80 years ago appears to show that the historical shift that Paasikivi was anticipating aroused in him a degree of patriotic solemnity as well as surly derision towards the Soviet Union. The mind of the old man was racing and writing to Ryti he allowed his emotions surface:

“It is a matter of life and death for us to be part of the Nordic bloc. I have no prejudices against the Soviet Union or Russia – I studied in Russia as a young man, and I am well versed in classical Russian literature and culture. I will do my utmost to maintain good relations with the Soviet Union. But if we remain within the sphere of her influence it will spell our demise. I haven’t the slightest doubt about this. We can trade here and engage in all kinds of relations. That was the case during the Russian rule. But the 100 years that we were part of Russia left us with nothing except a few culinary curiosities – the blini, caviar, bortsch and a few other dishes. And that is how it should be in the future. To the contrary, we distanced ourselves from Russia more and more each decade. Because this is a completely different world, and it does not suit us, it will kill us.”

Paasikivi reiterated these thoughts in his diary in September 1948, six months after the signing of the YYA Treaty: “The cultural and social life is different from ours in the Soviet Union, the Russian language is – fortunately – strange to us, and their entire lifestyle and all ideals are different from ours. It is a foreign world. We are part of the Nordic Countries and the Western sphere.”

The messenger

The utopian aspirations of forming a union with Sweden were quickly laid to rest following the scornful responses from Germany and the Soviet Union. However, this did not stop Paasikivi from continuing to seek Western affiliations, albeit strictly behind the scenes. Of all of the people in the world, he found support in Eljas Erkko, his longstanding adversary from the times of the split of the Finnish Party in the early years of Finland’s independence. The Erkkos sided with the Young Fennomans while Paasikivi remained in the ranks of the conservatives Fennomans, which later became the Coalition Party. Their relationship was not made any warmer by Paasikivi’s accusation of Eljas Erkko’s lack of competence as a foreign minister. Paasikivi was of the view that the Winter War was Erkko’s fault, and he did not keep his opinion a secret.

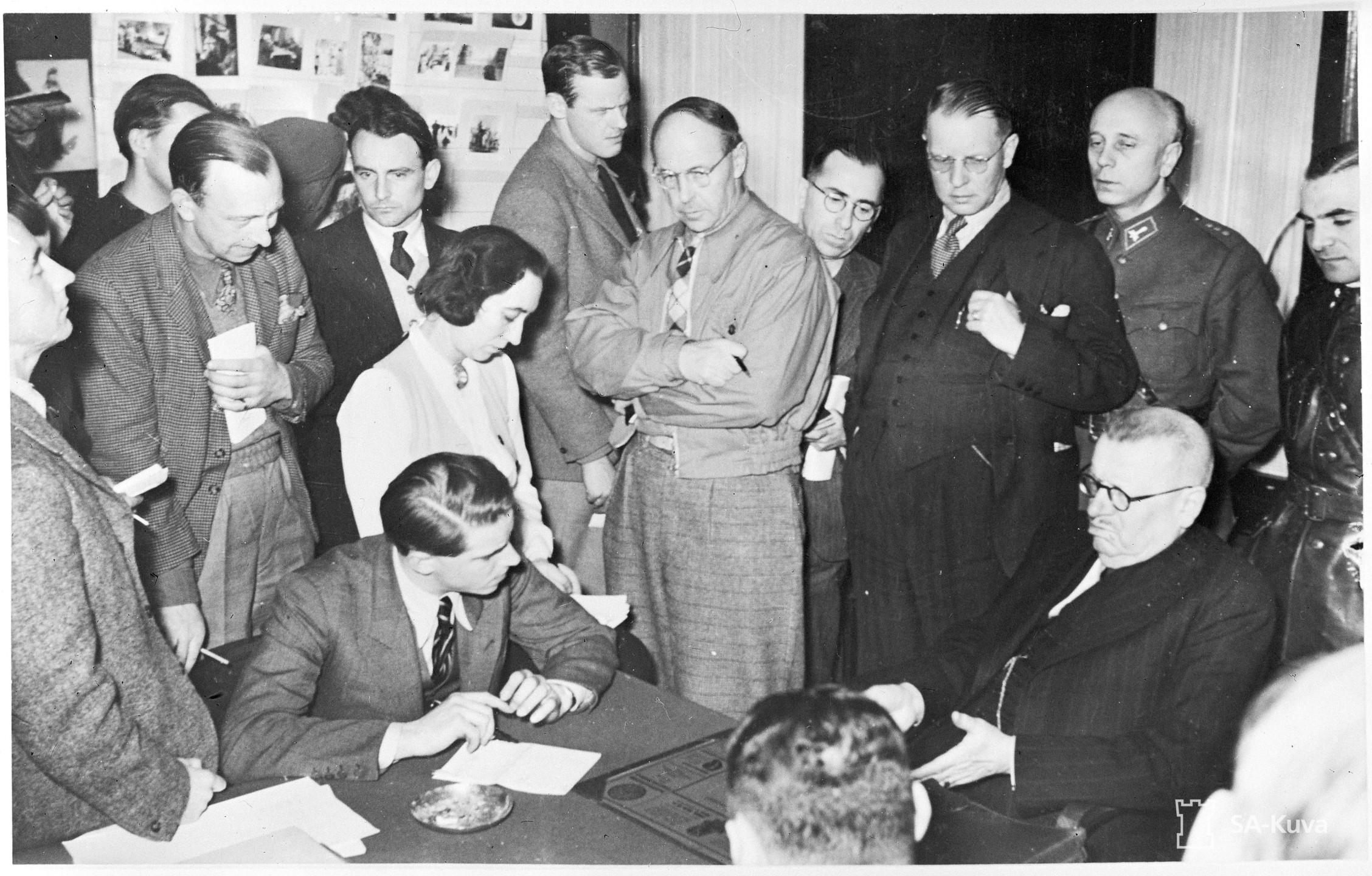

However, after the Continuation War, Erkko served as Paasikivi’s messenger to the United States. In May 1948, when preparing yet another trip to Washington, Erkko paid a visit to Paasikivi to listen to the President’s assessment of the situation in support of the discussions to be held with the US representatives.

Paasikivi was keen to communicate that the YYA Treaty was not seen as a threat in Finland, because it “acknowledged our particular position. It does not concern our democratic form of government, which will remain in force. The elections will be free. We will not relinquish our Western system: should Russia ever violate it and fail to abide by the agreements, we would turn to the UN and the general world opinion.”

The President was testing Erkko’s reliability as a messenger. He casually threw a curveball, mentioning the theoretical possibility of a war between the US and the USSR, and said that in that event “I think we would have to side with Russia, even if we thought that Russia would lose.” Erkko said he agreed. Erkko had passed the test and Paasikivi noted: “This was good to hear.”

The breakthrough

Paasikivi’s covert communications with the West were reciprocated. Finland was quickly accepted as a member in the World Bank and IMF, followed by memberships or partnerships in several cooperation bodies of the UN and the Western financial world. The Soviet Union showed no reaction, because these organisations were at that point considered in Moscow to be bodies operating under the wing of the UN and not a battle ground for the Cold War, as they would be later on.

In mid-July 1948, the US Ambassador Avra M. Warren told Paasikivi that, as an export partner, the US government had decided to give Finland a “different status from the rest of the Eastern bloc”, because she had shown that she was willing to retain free, democratic rule.

Warren intimated that his government was willing to support, and where possible, strengthen Finland’s independence. Paasikivi wrote down the Ambassador’s words verbatim in English .Warren noted that, particularly after the general election that ended in the defeat of the Communists, the US considered the development of Finland’s prosperity to be very important.

However, at the end of March 1948, the Finnish foreign ministry sent a concerned request for clarification to Washington owing to the rumours that President Franklin D. Roosevelt would have allowed Finland to fall into the Soviet sphere of influence at the Tehran Conference in the final stages of the Second World War.

Foreign Secretary George Marshall immediately responded that his ministry had no knowledge that such an agreement existed, emphasising his message by using a double negative. On repeating the question in October 1950, Finland received the same response. The assurances were supported by the fact that such agreements were starkly against normal US policies.

UN membership

Initially, Paasikivi took a reluctant view of Finland joining the UN. In early August 1949, he made a note of what Finnish diplomats had experienced at a negotiation situation that had occurred in Geneva. The leader of the Soviet delegation reminded his Finnish counterpart of “our friendship agreement” and expressed the hope that the Finnish delegation would support the Soviet Union “in important questions of principle.” Paasikivi bitterly noted: “This was just a taster of the difficulties we will be encountering at UN meetings.”

In October 1949, the Soviet Union decided to treat Finland like one of the many other countries awaiting the approval of the membership in the UN. The Kremlin threatened to prevent the membership of these countries if the West rejected the memberships of Soviet allies. Paasikivi was also worried about the possibility that the Soviet Union’s efforts to blackmail the UN could fail, in which case the Soviet Union might leave the UN. In that situation, Finland’s membership would be automatically accepted, as only the Soviet bloc was against it. However, it would also mean that the UN would be deemed by Moscow to be an anti-Soviet alliance, which under the Paris Peace Treaty Finland was prohibited to join.

By the end of 1952, Paasikivi’s reservations about the UN membership began to abate. It might provide at least some support to small countries in their attempts to have a voice in the new forum. “We must clutch at every straw […]. If the UN disappears, we will be left more orphaned and alone than we otherwise would be.” Soon Paasikivi was of the mind that “we are gradually getting to a point when it is time to join the UN. It would be a new signal of the normalisation of our situation.”

In early September 1954, the Finnish government was taking stock of its ministers’ attitudes towards UN membership. Foreign Minister Urho Kekkonen predicted that Finland would be rejected, “because a conflict between the blocs still exists”. Paasikivi’s thunderous comeback was: “If they choose us, we will go.”

By the time Finland was preparing for her debut at the UN in March 1956, Paasikivi had already been won over. “It is better that the UN exists than that it doesn’t […]. I think we should base our actions on rational causes. If that allows us to support the Russians, that’s all well and good. If not […], we must refrain from voting, if possible. If this is not possible, we cannot help but vote against the Russians.”

Paasikivi estimated that Finland would not have to succumb to Soviet authority at the UN. Refraining from difficult votes would be seen as a neutral gesture, and there was always the option of voting against the Soviet Union. It would appear that Paasikivi saw the Western bloc as the driving force within the UN and was seeking a kind of herd protection from the global organisation.

Paasikivi’s doctrine

At the end of July 1950, Paasikivi discussed the defence political report submitted by General Erik Heinrichs with Prime Minister Kekkonen and Foreign Minister Åke Gartz. The most perilous of the scenarios that Heinrichs had painted was the possibility that US bombers would fly over Finland to their targets in the Soviet Union.

Heinrichs assumed that the Western powers might boost their flanking operations by attempting a landing through Southwestern Finland. Heinrichs did not recommend that Finland rely on Soviet backing when defending against a Western offensive. He proposed that, instead, Finland should upgrade its air defence and mobile coastal defence systems.

Paasikivi continued laying the ground for the national defence policy at a meeting attended by all key cabinet ministers. The President discussed Heinrichs’ report as well as Commander of the Finnish Defence Forces Aarne Sihvo’s situational reports on international politics.

They emphasised the importance of improving the defence readiness if Finland were to meet her treaty obligations. Paasikivi justified Finland’s duty of defence with the country’s independence and the Paris Peace Treaty. The obligations imposed on Finland under the YYA Treaty, Paasikivi omitted.

After autumn 1950, Paasikivi stopped making notes of his deliberations regarding defence questions for a long time. Only in autumn 1954, when the tensions created by the Korean War began to subside, did these notes reappear. He wrote that the possibility of war had to be acknowledged, although it would not happen “in his time”. The stronger the defence organisation, the better Finland’s chances of avoiding a “Russian occupation”. The Russians had to be dealt with on a political level, because on a military level they could not be challenged. “Naturally, we must maintain an army that is as well-resourced as possible.”

Towards the end of his term, in late summer 1955, Paasikivi’s concerns about Finland’s defence capacity again grew. He used Kekkonen as a sounding board for his thoughts. If the Russians did not honour the agreements and resorted to the use of military force, “we must choose a different course of action than the Czechs, the Polish etc. did, and we must make this clear to the Russians”. In other words, he was talking about the readiness to defend the country against the Soviet Union and this readiness also had an ideological dimension. If “the Russians insist that everyone preaches the same creed,” we will not accept it.

A few days later, the president repeated this to Emil Skog, Minister of Defence and K.A. Heiskanen, the new Commander of the Defence Forces. This, in effect, was the testament of the old president to the senior leadership of the country’s military security. Paasikivi’s defence doctrine was about defence against assistance provided under the YYA Treaty that would come in a form of a massive land offensive.

The command that was never given

The literature paints an oddly confusing picture of the underpinnings of the Finnish defence policy during the Cold War. While Paasikivi’s legacy, which he passed on to his closest circle, appears only to set the baseline for the policy, in reality its impact was felt much more widely.

The Revision Committee, which was set up to deliberate the country’s post-war defence policy, proposed in 1949 that Finland should prepare for a massive land offensive; implicitly, this meant preventing a Soviet invasion. This defence doctrine always co-existed with the YYA Treaty, the letter of which does not recognise the possibility that the Soviet Union would attack Finland and, even less, that Finland should defend itself against such attack by military means.

Yet it was obvious and professionally inevitable that the Finnish military leadership should devise plans for the eventuality that, as Paasikivi had envisioned, the attacker would turn out to be the YYA partner.

For a long time, documents to support this could not be found where they were expected to be kept. This led to the conclusion that, for the sake of protecting foreign relations, there had been a reluctance to document such dangerously explosive defence plans. According to several doctoral and other similar exhaustive studies, it long appeared that the Defence Command Archives simply did not contain any other defence plans than those made against Western threats.

However, there were also rumours indicating the opposite. General Ermei Kanninen, who had served in key positions in the senior military leadership during the Cold War, said that the concentration orders against a Soviet offensive had been carefully prepared. They had not been documented, however, or stored in the safes of the commands. The generals in charge of the plans memorised them and could recite them even if woken in the middle of the night, Kanninen assured.

The sources referenced in the publication published in May 2018, marking the 100th anniversary of the Finnish Defence Forces, shed some new light on the mystery, suggesting something slightly different to what Kanninen had related. Professor Vesa Tynkkynen and Adjunct Professor Petteri Jouko showed in their article that the first operative order against an offensive from the East had been approved in summer 1952, soon after Paasikivi had held his first defence policy discussions with the ministers.

The most extensive of the plans were prepared for offensives from both the east and the Gulf of Finland. The defence operations had been staggered into three zones, with the general objective of securing at least the southern and western parts of the Finnish territory. In the final version of the preparations for various defence scenarios, precautions were also made against a surprise attach to capture the command centre, which is precisely what happened in Czechoslovakia in August 1968, only shortly after the approval of the plan.

The transition to a regionally organised defence system in the late 1960s changed the situation. The new defence structure showed great political savvy. The orders would no longer have to include sensitive speculations about the direction from which the offensive might be originating. The regional commands, which formed the backbone of the new defence organisation, would simply defend themselves against any threat from any direction.

Real realism

Paasikivi’s covert Western sympathies and military readiness were kept as insider information for decades. When his diaries were published in the mid-1980s, the official image of a president who was friends with the Soviet Union gained another dimension that revealed an unwaveringly realistic statesman, although this hardly came as a big surprise to anyone.

It had long been the wish deeply nurtured in the national psyche that Paasikivi had been like a radish: red on the outside, white on the inside. This was not just a living urban legend, but also a view that the Soviet leadership shared. A.N. Abramov, number two in the Scandinavian Department of the NKID in the early 1950s, had said that Paasikivi was the Soviet Union’s “strongest and most intelligent enemy”.

In conversation with Kekkonen in early December 1956 at the Salus Hospital, two weeks before his death, it was as if a shadow of a Machiavellian character had made a brief appearance at his hospital bed. Paasikivi advised his successor: “We must manage our policies so that we stand to gain from the internal deterioration of Russia but never to lose when it grows stronger.” Paasikivi’s key message was apparently correctly understood in Moscow and Washington alike. The former Foreign Minister Molotov reminisced in the 1970s about his post-war policy towards Finland: “Oh how gentle we were with Finland! We were wise not to invade them. It would have left a lasting wound… People in Finland are stubborn, very stubborn. Even a small Finnish majority would have been dangerous.[…] We did not manage to democratise Finland any more than we did Austria.”

The article was first published in the periodical Kanava (7/2020).

Jukka Tarkka, D. Soc.Sc., has served in the senior management of Otava Publishing Company and Yhtyneet Kuvalehdet and as an MP for one term. He has published six books on political history alongside his professional career and another nine since his retirement. Over four decades, Tarkka has written more than one thousand columns for Helsingin Sanomat, Suomen Kuvalehti and leading regional newspapers.