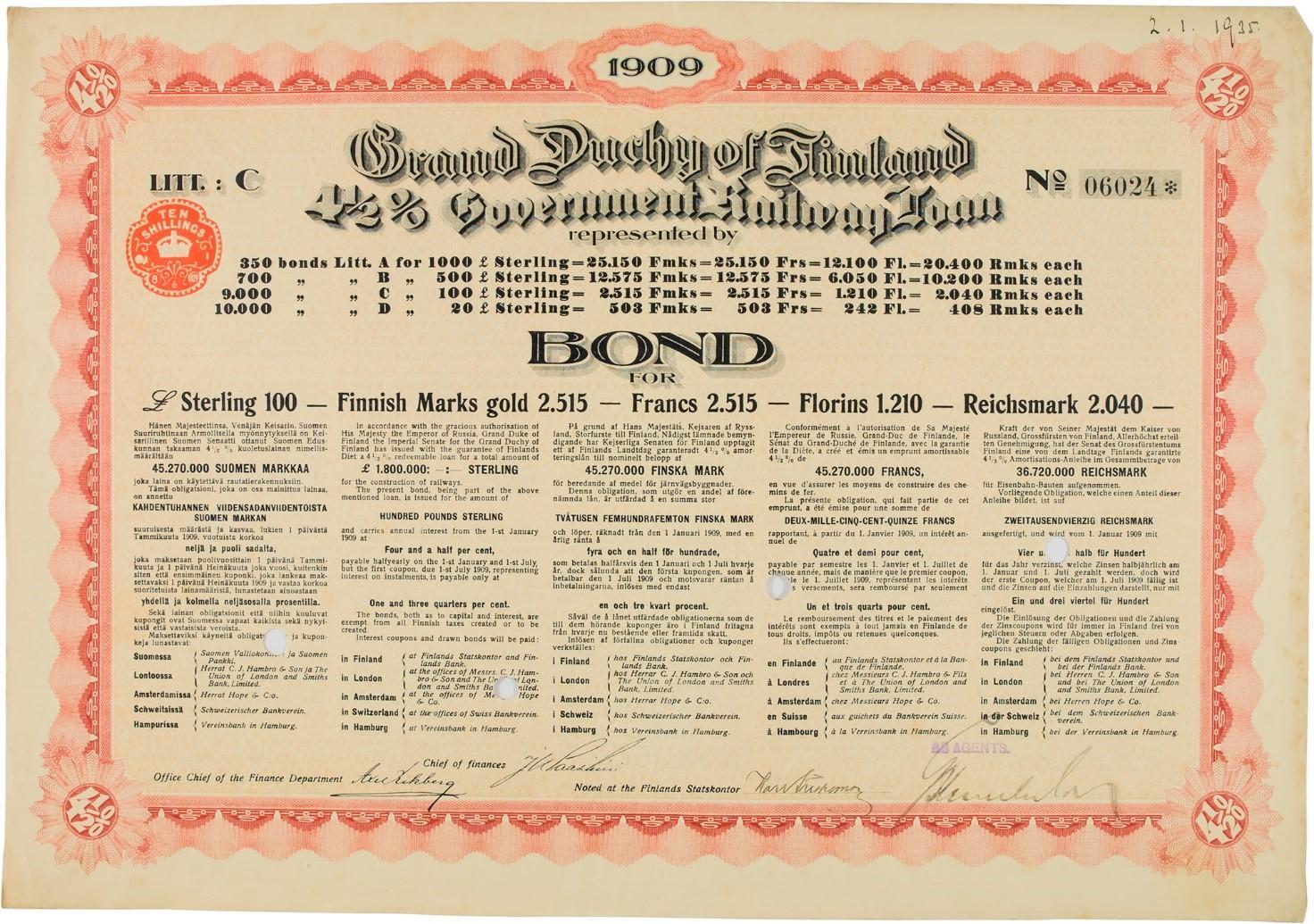

Paasikivi showed keen interest in central government borrowing in the early years of his long career and wrote several extensive articles on the matter for various publications. While serving as the Head of the Economic Division of the Senate 1908–1909, he was also presented with a brief opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of international capital markets and global economic and political trends. During his service in the Senate, Paasikivi was also responsible for the last foreign issue of the government bond of the Grand Duchy of Finland in London.

Government borrowing during autonomy

Paasikivi’s interest in government borrowing was understandable. He developed a wide interest in current economic and political questions in his various roles as a rising politician of the Finnish Party, and as an activist in the Finnish Economic Society, General Director of the State Treasury, the Head of the Economic Division of the Senate and a long-serving Director of Kansallis-Osake-Pankki.

Paasikivi’s interest in government borrowing was also undoubtedly reinforced by its great significance as a driver of Finland’s economic growth. The Senate of Finland borrowed regularly from the international financial markets during the last few decades of autonomy. Foreign borrowing was a factor spurring Finland’s economic and political awakening. Secured by the borrowing, the state could finance the construction of a nationwide railway network. At the same time, the Senate supported the foreign currency reserves of the Bank of Finland and markka’s adherence to international silver and gold standards. Securing the availability of foreign capital became a central economic objective for the Senate.

The healthy liquidity of the European bond markets enabled the Senate to adopt the policy of borrowing. The idea of government bonds was conceived in the early Italian city states, but a systematic and transparent mechanism to manage and fund public spending emerged as a result of the Glorious Revolution of 1688 in England. Following the example of England, government bonds became a reliable and valued investment. The multinational, originally Frankfurt-based Rothschild banking house led the integration of European financial markets in the 19th century, with the result that plenty of capital from capital surplus countries shifted to capital-deficient emerging economies. London grew into the largest financial centre in history.

The autonomous Grand-Duchy of Finland issued its first ever foreign bond in 1863 on the German market. For the next quarter of a century, Germany was the main source of lending, almost exclusively brokered by the Rothschilds. This was followed by a sudden change in tack as the Senate decided to move all its government bond issues from Germany to Paris in the 1890s. The reason for the sudden move lay in power politics – Russia also moved to another source of financing after the League of the Three Emperors dissolved – and the differences in the demand for capital in Germany and France. In the French market, the Senate of Finland relied primarily on Crédit Lyonnais, which was represented in the north of Europe by Stockholms Enskilda Bank, headed by K.A. Wallenberg, who knew Finland well.

Confidence in the Grand-Duchy

At the turn of the 20th century, government bond markets formed the backbone of the financial system. The market quotations for the bonds were considered a key indicator of a country’s economic and political performance and credibility. According to the Austrian economist Eugen Böhm von Bawerk, the level of a country’s cultural achievement was reflected in the interest rates of its bonds. He argued that the lower the interest the higher the people’s intellectual and moral capacity.

In Finland, too, the interest quotations of the country’s own government bonds became a major economic barometer, but also something a lot more significant. The confidence of markets was interpreted as a symbol of Finland’s autonomous identity as a country which was separate from the Russian Empire. Johannes Gripenberg, a civil servant in the Office of the Minister–Secretary of State for Finland, wrote from St Petersburg to Professor Yrjö Sakari Yrjö-Koskinen describing how the Russians were in awe of Finland for her well-organised administration, competitive industry and finances based on solid foundations as well as for the confidence of the international loan markets that should be the envy of many rich countries.

The bonds issued by the Senate were quoted in the stock exchanges of major financial centres alongside the bonds of other states, emphasising Finland’s identity as a state in its own right. International banks, most prominently Crédit Lyonnais, wrote positive reports of the “prudent management” of Finland’s public finances, treating Finland as a clearly separate entity from the Russian Empire. In the marketing materials sent by the headquarters of Crédit Lyonnais to its local branches in France and Algeria, Finnish government bonds were promoted as one of the most secure bonds on the market, together with Swedish, Danish, and Norwegian bonds.

Furthermore, the bond issues were exclusively targeted at western broker banks and investors. The symbolism on and the documentation of Finnish government bonds emphasised Finland’s autonomous and separate status. In this respect, foreign borrowing was part of the process described by Professor Osmo Jussila, in which Finland started inching, step by step, towards independence from the Russian empire from the 1860s onwards, both on a practical and a symbolic level.

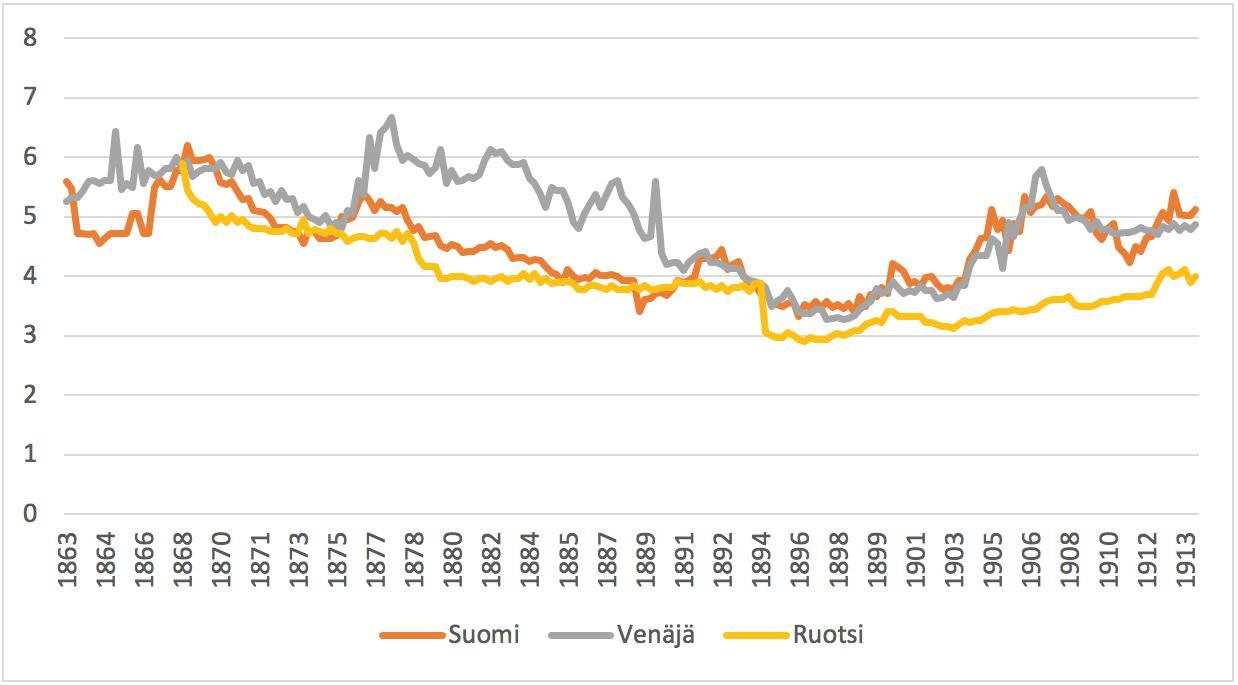

The hey-day of the Finland’s reliance on foreign capital markets coincided with last few decades of the 19th century. The nominal interest rates fell and the yield spreads between different government bonds narrowed down on the newly integrated financial markets anchored to the gold standard. It was also during this period that Finland’s credit rating reached its peak as the yields from its bonds were on par with other Nordic bonds, in other words, the credit risk associated Finnish bonds was considered as low as for other Scandinavian bonds. This confidence was due to Finland’s disciplined financial policy that avoided excessive borrowing and Finland’s adherence to the international gold standard alongside all major economic powers. The measures that Russia took to bring Finland more firmly under her control gradually affected the way the Grand-Duchy was perceived in the world financial centres. As a result of the Russo-Japanese War and political unrest in Russia, the interest rates of Russian bonds took an upward turn, taking the Finnish bond interests with it. This meant that the yield differential between Finnish and Swedish bonds widened.

Government bond yields (%) 1863–1914. The interest rate of Finnish central government bonds in international stock exchanges departed from the that of other Scandinavian countries and followed the quotations of the Russian government bonds.

The increased risk associated with Finnish bonds compared to its western neighbours caused heated debate in Finland, in which Paasikivi participated by writing a piece in the newspaper Uusi Suometar. Paasikivi presented an exhaustive overview of the trends in interest rates since the 1880s. He wrote that the weakening of Finland’s position coincided with “the new chapter in the relations between Russia and Finland”, confirming, in Paasikivi’s view, the general perception that the deterioration in the relations between the nations had a negative impact on foreign borrowing. Perhaps Paasikivi was not in a position to foresee that the development that he had identified afresh would remain the status quo for more than half a century, as the proximity of Russia/the Soviet Union undermined the confidence of Western financial centres in Finland.

J. K. Paasikivi in charge of foreign borrowing

Paasikivi’s article in Uusi Suometar came after a period during which he was personally involved in negotiating the price of bonds. As General Director of the State Treasure since 1903, J.K. Paasikivi served as the Head of the Economic Division of the Senate – in present-day terms as the minister of finance – in Edvard Hjelt’s Senate in 1908–1909. Paasikivi’s first decisions in his new role concerned the issuance of a new bond loan to finance railway infrastructure investments. Funds were desperately needed but obtaining loans in the new market situation proved to be far from easy.

Paasikivi also faced two domestic problems that he perhaps initially would not have known to link with foreign borrowing: prohibition and the Jewish question.The Senate was planning to issue a new bond loan in Paris in 1908, as it had done systematically since 1895. The terms were quickly agreed upon, but at the last minute Count F. de Chevilly, who represented the banks, travelled to Helsinki to discuss the prohibition plans with Paasikivi. According to de Chevilly, France would not grant the legally required permission for the issuance if the exportation of French wines and other alcohol products to Finland would stop. In his capacity as the minister of finance, Paasikivi should have promised that the prohibition would not go forward. Paasikivi felt, however, that he was not in a position to do so, and to his great disappointment, the issuance of November 1908 was cancelled.

Once the doors of the Paris markets had closed, Paasikivi turned to London. Negotiations with the British C. J. Hambro & Son on the first sterling bond issuance progressed swiftly until Paasikivi, just before Christmas 1908, received a telegram from Hambro with a warning that the issuance was under threat. The reason was the reports in London newspapers stating that Finland was mistreating its small Jewish minority and that it planned to restrict the right to practice Jewish religion in Finland. Paasikivi reacted with speed and together with Senator Kaarlo Castrén sent a telegram to Hambro insisting that the rumours were not true and that, to the contrary, the Senate was preparing a bill that would safeguard and extend the rights of the Jewry in Finland. Crisis was averted and the bond issue was successful.

Paasikivi’s experiences are illustrative of two salient features of the politicised financial markets of the day. Trade (and power) politics had a strong impact on the functioning of the markets and the availability of funding, and that questions related to the treatment of Jewish people were reflected on the financial markets, as many of the most powerful banks dominating the financial system were under Jewish ownership.

The price of new bonds settled at a lower level than expected, which was a cause of certain criticism in Finland. Paasikivi was not satisfied with the development of the Finnish bond prices but stated that the emission price was the best that could be achieved at the time. The significance of bonds to the national economy was vast, as it accounted for more than one half of the annual state tax revenue.

Ultimately, the main thing for Finland was that an important loan could be secured on the markets, as Kauppalehti stated in its editorial of 13 January 1909: “The obtaining of the state loan has on our behalf been steered by the new Head of the Economic Division of the Senate, Senator J.K. Paasikivi, who has shown to be a man of great efficiency in the negotiations concerning the matter.”

Paasikivi’s thoughts about central government borrowing

The progressive ideas of the social and land reform held by Paasikivi and the conservative Fennomans in general were in line with the government policy of foreign borrowing during the autonomy.Backed by the capital secured by the state, the construction of the nationwide railway network could go forward, which in turn brought great improvements in the standard of living in the rural areas of Finland. The access to raw materials in the forestry sector improved and agriculture moved to commercial trading.

These achievements supported Paasikivi’s own ideology that government borrowing was acceptable if spent on the right causes. According to Paasikivi, government borrowing was desirable only for productive purposes that would lead to growth in the production and wellbeing of the country. If these criteria were met, it was also advisable to avoid excessive taxation and, instead, rely on borrowing, as Paasikivi wrote in 1928. In his view, capital should not be transferred from private businesses to be publicly invested, as public undertakings would never yield similar results as private entrepreneurship. These thoughts amalgamated Paasikivi’s approach to government borrowing and his social reformistic and liberalistic ideals. While in charge of the last foreign bond issue of the autonomous Grand-Duchy, Paasikivi had the opportunity to make his mark in the investment in socially important infrastructure investments. At the same time, the role placed him in a vantage position to observe the workings of the international financial markets at a time when the international atmosphere began to increasingly affect the price setting and direction of capital flows on the market.

Mika Arola, D.Soc.Sc., is a Deputy Director, Risks and Strategy, at the State Treasury.