Anna Forsman (1869–1931) was J.K. Paasikivi’s first wife from 1891 until her death in 1931. She served as the headmistress of Lahti Adult Education Institute and was a teacher at the Finnish-language co-educational secondary school. After the family moved to Helsinki, Anna devoted herself to raising their four children and supporting her husband in his many political and public positions. She died of tuberculosis at the age of 58.

Anna Matilda Forsman was born in February in 1869 at Kårböle, in then Helsinki Rural Parish, as the third daughter of School Master Israel Forsman and his second wife Anna Loviisa Toivonen. Her upbringing was strictly religious. In addition to her four sisters, she also had four older half-sisters from her father’s first marriage. One of Anna’s half-sisters, Helena Forsman was fostered after her mother’s death by her godmother, the dean’s wife Nathalie Crohns and served, among other positions, as the headmistress of Nya Svenska Samskolan, a Swedish-speaking co-educational secondary school.

The proteges of a dean’s widow

The connection between Anna’s family and the Crohnses remained close for decades. Prior to his position as a school master, Israel Forsman had served as a labourer at the Crohns’ rectory in Helsinki Rural Parish. In the 1870s, Forsman rented the Huopalahti Manor (Grejus gård) from the City of Helsinki. Anna attended a Swedish-speaking school and finishing the school in 1883 with excellent grades, she continued her education at Nya svenska samskolan.

In 1886, Israel Forsman was forced to file for bankruptcy. The Forsman’s entire estate was sold on public auction. At that point, Anna was a 17-year-old secondary school student, while her youngest sister was nine. Israel Forsman died in 1889, and his estate filed again for bankruptcy. Anna’s mother moved to Stenkulla in Tikkurila with Anna and the younger children to live in the Crohns’ household.

A woman at university

In Anna Forsman enrolled in the Imperial Alexander University (present-day University of Helsinki) in the Faculty of Philosophy’s Department of Physics and Mathematics in autumn 1890. Despite her Southern Finnish and Swedish-speaking roots, she joined the student association of Eastern Finnish students (Savo-Karelia). In the late winter of 1893, Anna participated in a skiing trip for Savo-Karelia and Tavastia students associations, where she met a renowned Fennoman activist named Juho Kusti Paasikivi.

That same spring, Anna Forsman had given a long address at the Savo-Karelian student association on the situation of female university students. She demanded that female students should be charged the normal membership fee, which would entitle them to vote at the student association meetings. Female students should also be freed from the “special supervision by the Rector”. In April 1893, Anna Forsman was elected to the Student Union’s committee as the only female member with nearly 300 votes. In the committee election of the following spring, she won even a higher number of votes.

”Where there is love, there are riches”

Instead of science, Anna Forsman concentrated on studying the Finnish language. Back in spring 1893, she had written to the “esteemed and greatly missed” Paasikivi and invited him to join her for the summer in Kangasala in Tavastia as her Finnish teacher. The 22-year-old history graduate was in love and paddled every day in his canoe from the house of his former classmate K.A. Franssila, where he was a guest, to see Anna at Sarkola. They continued to correspond with each other in Swedish. They made some progress: Anna Forsman and Juho Kusti Paasikivi became secretly engaged the same summer, although the official engagement did not take place until spring 1895.

Their relationship had a dramatic impact on both of their lives. Juho Kusti decided to switch his subject from the humanities to law in order to guarantee an adequate income for his future family and Anna supported his decision all the way. When Juho Kusti occasionally found himself short of money and considered taking up a position as a newspaper editor in Jyväskylä or as a bank manager in Lahti, Anna encouraged her fiancé to concentrate on his doctoral dissertation. “Where there is love, there are riches,” she wrote to him in plain Finnish in September 1893. “You will become a doctor as has always been your plan, because otherwise I will not become a doctor’s wife. You must not give up on your dreams because then I would regret our engagement.”

On her own studies, however, Anna gradually gave up. In autumn 1893, she accepted the position of amanuensis at the University Library, which had initially been offered to Juho Kusti. Both Anna and Juho Kusti were penniless: both had fathers who had been forced to auction their entire estates shortly before their deaths. In addition to Anna, her family also had high hopes for her fiancé, who seemed destined for a bright future. In autumn 1895, Helena Forsman wrote to her sister: “I am overjoyed thinking of the day when I can finally call you ‘my sister, a senator’s wife’.”

Meagre years in Lahti

To save on expenses, Juho Kusti returned to Lahti. He had been one of the leading founding members of Lahti Adult Education Institute although he was unable to accept the position as its first ever director in autumn 1893 because of his university studies. Anna enrolled in the Kangasala Adult Education Institute in spring 1894 to improve her handicraft skills and practice giving lectures. In July 1894, the headmistress of the Kangasala Adult Education Institute advertised in the local newspaper Aamulehti renowned visiting speakers at the institute including Hilda Käkikoski and Fredrika Wetterhoff, and: “Our third speaker is university student Anna Forsman who with her charming demeanour has captured young and older audiences alike. During her studies in handicrafts, she has also lectured in natural sciences.”

On these merits, Anna Forsman was appointed the headmistress of Lahti Adult Education Institute for the academic year 1894–1895. She gave talks on geography, health and hygiene and botany, led women’s crafts and gymnastics groups, and assisted a male colleague in teaching calculus. Anna spoke at the opening ceremony of the new academic year in early November on “the relationship between practical and knowledge subjects when teaching at an adult education institute.” The following year, Anna taught not only handicrafts but church history, health and hygiene, singing, and gymnastics.

While the students were initially very fond of their headmistress and even gifted her in 1894 with a gold watch, teaching took its toll on Anna’s frail nerves and she spent periods of time recuperating in a spa sanatorium in nearby Heinola and in Sweden. An expensive trip to Enköping, Sweden, in the autumn term of 1895 also placed a strain on the fiancé. When Anna demanded that Juho Kusti should come and meet her in Sweden, her fiancé replied in a letter: “My darling, I cannot possibly come and meet you any further than Riihimäki, because there isn’t enough money.”

Recurring sick leaves and a “difficult character”, of which Anna was herself aware, led to spiralling conflicts with the institute’s director Franssila and eventually with the sponsor of the institute, August Fellman. Anna’s career at the adult education institute came to an end in summer 1896. However, Juho Kusti was able to arrange a position for Anna as a teacher in the newly established Finnish co-educational secondary school in Lahti.

In May 1897, Juho Kusti completed his Master of Laws degree and on 1 June, Anna and Juho Kusti were married at the Crohns’ rectory in Stenkulla. At that point, Juho Kusti was serving as a judge in the Hollola jurisdiction and as a police chief in Asikkala, as well as a private attorney in Lahti, so the family remained in Lahti. In the late winter of 1898, Anna fell pregnant and gave up her position as a teacher the next autumn. Their daughter Annikki Aarre was born on 20 November 1898 in Helsinki.

A mother of small children

The first few years in Helsinki were financially challenging with Juho Kusti providing for his family with low-paid teaching jobs while writing his doctoral dissertation. Research took him abroad for lengthy periods: he spent the summers of 1898 and 1900 in Stockholm at the National Archives and the summer of 1899 studying at the university of Leipzig in Germany. After this, new positions and public offices took up the majority of his time.

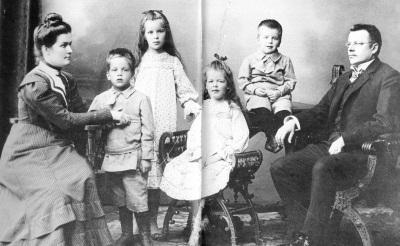

Meanwhile, Anna spent her time mainly in the nursery looking after their growing family. Annikki was a little over a year old when the Paasikivi’s second daughter Wellamo Anna was born on 22 January 1900. The two- and three-year-old sisters welcomed their first baby brother Juhani Wilhelm on 30 November 1901. The youngest of the four children, Varma Juho was born on 1903, making Anna a mother of four children all under four. Although she had the help of maids and family, her nerves were under a lot of strain during this period. While Anna was the person to lead the family’s evening prayers, memoirs also mention her as a harsh physical disciplinarian.

The wife of a senator and director general

The family’s financial situation and social standing improved after Juho Kusti Paasikivi’s doctorate in law was accepted in 1901, and his career took a decisive upward turn. The rise in status meant that Anna also began to participate more in public life: in 1905, she joined a national association promoting school meals, in 1906 the Finnish Literature Society and in 1906 she was elected as a member of the committee of the women’s organisation under the Helsinki chapter of the Finnish Party. Women had been given the right to vote and all political parties had launched campaigns to win women’s votes in the next general election.

Anna Paasikivi supported the Finnish Party’s election campaign with great enthusiasm while her husband was also running a successful campaign in his own constituency. In March 1907, Anna gave a speech at a women’s event of the Finnish Party, in which she praised the candidates Aleksandra Gripenberg and Hilda Käkikoski with great eloquence: “… this very moment, as we are standing at the gates leading into a promised land, this very moment, as we as human beings in our own right walk side by side with the other sex, sharing the burden and the yield, this very moment, as we deeply understand how strong your confidence was that the light and the freedom would eventually come, how great was your love for us who were still slumbering!”

When Juho Kusti Paasikivi was appointed Head of the Economic Division of the Senate, (minister of finance) in 1908, Anna’s role in the election campaigns and national general assembly of the women’s organisation of the Finnish Party became even more visible. In 1911, she was elected the chair of the women’s committee. In the 1910s, Anna improved tremendously as a public speaker and writer, and Juho Kusti had every faith in his wife’s competence. When Paasikivi declined to stand in the general election of 1913 and wanted to step down from the leadership of the Finnish Party, he arranged for Anna to become his deputy in the party council and wrote to his wife, who was once again recuperating in a spa in Germany: “You can take care of my business on my behalf.” In 1916, Anna Paasikivi was elected as an ordinary member of the party council.

At home with the great and the good

In 1910, Juho Kusti joined the housing company Oiva, which was developing a block of flats in Nervanderinkatu street. The new residents moved into the state-of-the art flats in the building in May 1911, although major repairs were to be endured for some time after.

Most of the notable men whose families moved into the building knew each other from university, politics, or business and many of their wives were friends of old or even family. Anna Paasikivi’s closest friend was Elsa Melander, wife of Gustaf Melander, the Director of the Finnish Meteorological Institute. Else was the granddaughter of Rev. Crohns and knew Anna from their time in Stenkulla. Anna trusted in Elsa’s homemaking skills and often asked for her advice. During the years when Anna was ill, her favourite food were Elsa’s preserved blueberries and a healthy soup she made from them.

Other ladies residing in Oiva considered Anna an industrious and impulsive person but rather lacking in the area of housekeeping. The Paasikivis ate modestly during the week, but when they were having guests they would order food and sandwiches from the Kämp Hotel. Juho and Anna’s loud arguments and their children’s extremely strict upbringing caught the neighbours’ attention. The bank manager’s children seldom had any pocket money, and they would be routinely punished for school grades that were less than excellent. After the family moved to Erottaja in 1921, Anna started giving dance lessons to her daughters and ran a gymnastics club for the Kansallis-Osake-Pankki board members’ wives and hosted extravagant parties.

During the spring of 1918, during the period of Red Terror, the family was still living in Oiva in Nervanderinkatu. Juho Kusti was wanted by the Red Guard and had gone into hiding at their friends’ home. Their daughter Annikki was among the women polytechnic students who smuggled arms and ammunition to White Guard troops hiding in Helsinki. The torment ended with Count von der Goltz’s German troops landing in Finland. The count became the Paasikivis’ family friend and Anna was asked to be godmother to one of von der Goltz’s granddaughters.

The mistress of Jukola

The inflation and food shortages following the First World War had made the Paasikivis consider buying their own farm. However, all their offers to buy farms were rejected by their Swedish-speaking owners due to the latter’s unwillingness to sell to Finnish-speaking buyers. In spring 1917, Anna Paasikivi wrote a scathing piece in the periodical, Suomen nainen, criticising such an attitude. The farm that the Paasikivis eventually bought in Kerava in July 1917 was also originally owned by a Swedish-speaking family. The Paasikivis renamed the farm Jukola Manor, as a tribute to Aleksis Kivi’s novel Seven Brothers, a key work in Finnish literature. Like the good mistress of a large farm that she aimed to be, Anna ran the Sunday school for the children in the area. When Juho Kusti was forced to remain in Tarto for months for the peace talks, Anna managed the farm and reported on the progress of work to her husband in letters.

Juhola’s garden and orchard, which spanned some two hectares, became Anna’s main project, although there was a gardener on the farm. The background to Anna’s love of gardening was explained in a story published in the magazine Joulujuhla in 1911, “The old lady who planted trees”. The story was probably loosely based on dean Crohns’ widow and the garden of Stenkulla, but the final sentence is pure Anna: “While you are still alive, love nature like it was your best friend – the one friend who looks after you after you are gone until the day when we will all be called to stand before the face of our Lord.”

Deathly disease

Anna Paasikivi’s persistent cough, which doctors had for years treated as catarrh, was finally diagnosed in 1926 as pulmonary tuberculosis. The disease had already been the death of many in the Forsman family. Anna’s youngest sister Lydia Maria Serenius, a mother a young family had died of TB in 1907 the age of 30. It was soon discovered that the Paasikivi’s youngest, the 23-year-old son Varma had also contracted the disease.

Anna and occasionally Varma were treated in Switzerland at a sanatorium in Agra. Anna did not want to be alone, so family and friends took turns visiting her. Anna was a difficult patient. Juho Kusti had to beg the chief physician not to discontinue her treatment although “my wife is terribly nervous and extremely lively (lebhaft).” When the treatment, which by then had lasted for more than a year, was terminated, Anna and her nurse were built their own accommodation upstairs in Jukola. In 1930, the family moved back to Helsinki to an 18-room villa designed by Annikki. In the new house, too, Anna and the nurse had their own rooms. The villa had a covered roof terrace, where Anna could rest in fresh air even during the winter.

Anna’s health deteriorated rapidly in the autumn of 1931. Juho Kusti, who was burdened by economic recession and the difficulties that Kansallis-Osake-Pankki had spiralled into, suffered from insomnia. Finally, a few days before Christmas, Anna lost her battle against the illness. She died at home at 9.15 in the morning of 22nd December 1931. She was 58 years old.

Juho Kusti wrote in his diary: I was in the bathroom, when Varma stepped in and said, covering his eyes with his hands: ‘It is over’. Anna had been extremely unwell the night before. She had called the nurse several times.− − Varma and I read at the usual hour at 1/28 in the evening the hymn ”Din sol går bort”.

Kirsti Manninen is an adjunct professor and writer. She has also written a play about the Paasikivis’ years in Kerava.

Sources

1. Helsingin pitäjän syntyneiden ja kastettujen luettelot 1851−1865 ja 1865−1880 SSHY [Catalogue of Births and Christenings in Helsinki Rural Parish 1851–1865 and 1865–1880 Finland’s Family History Association (FFHA)]

2. The newspaper and journal collections of the National Library of Finland

3. Paasikivi, Juhani: Monumentin sukua. Otava,1999.

4. V. J. Palosuo: Merkkimiesten talo. A history of a building where many notable people lived, including Hannes Gebhard, Lauri Ingman and J. K. Paasikivi. Kirjayhtymä, 1986.

5. Polvinen, Tuomo: J.K. Paasikivi. Valtiomiehen elämäntyö 1 1870–1918. WSOY, 1989.

6. Polvinen, Tuomo: J.K. Paasikivi. Valtiomiehen elämäntyö 2 1918–1939. WSOY, 1992.

7. Rumpunen, Kauko (ed.): ”Olen tullut jo kovin kiukkuiseksi.” J.K. Paasikiven päiväkirjoja 1914–1934. Kansallisarkiston ystävät – Riksarkivets vänner ry (Friends of the Finnish National Archives). 2000.