“The co-operative movement is proud to be associated with President Paasikivi as one of the celebrated champions of our movement.” These words were published in the Suomen Osuustoiminta magazine by Pellervo, the Confederation of Finnish Cooperatives, in late 1956 on the news of the recent passing of President Juho Kusti Paasikivi.

Over a period of six decades, Paasikivi had played several roles in the co-operative movement. Typical of supporters of co-operatives, Paasikivi was an ardent social reformist and one of the earliest advocates of the movement. He was a member of Pellervo and served as its legal counsel, secretary to the board and finally a member of the board. He became an expert and adviser on co-operative law, the author of co-op codes of conduct and handbooks and a founder and member of the board of governors of the Central Lending Fund of the Cooperative Credit Societies. In his new positions, he also had a role in providing funding for co-operative businesses. As the President of the Republic, Paasikivi acted as a national symbol of the movement, which at the time of his youth had served as a major facilitator the economic and social mobility for large sections of Finnish population.

The birth of the co-operative movement in Finland

The birth and expansion of the co-operative movement in Finland in the late 1800s and early 1900s were driven by widespread economic and social needs. The escalation of Finland’s political situation as part of the Russian Empire to crisis point also served as a trigger for the movement.

The 19th century was marked by innovations in technology and transport infrastructure, industrialisation, urbanisation, economic growth, and the evolution of the bartering and monetary economy. Social and economic disparity between different segments of the population brought social tensions close to a flashpoint. The position of workers and smallholder farmers was poor, which created a breeding ground for new thinking. Socialist ideas began taking root.

The unification of Germany and her rising political prowess altered the balance between the major powers, and this was also reflected in Finland. Russia tightened her grip on the Grand-Duchy on its periphery, a policy to which Finland reacted vehemently by seeking national unity.

Pellervo, the confederation of Finnish co-operatives was established in 1899 by a number of progressive private individuals with the aim of promoting the international co-operative ideology. The purpose of the movement was to unite people in economic pursuit, mutual businesses, and even in limited companies to share the fruits of successful endeavours among their members and thereby improve their financial and social standing. Hannes Gebhard, the key ideologue and organiser of the movement characterised co-operatives as enterprises whose basic idea was, by replacing private businessmen and the owners of capital, to generate profit for the members of the society whose economic activities generate these profits”.

In short, the evolution of co-operative societies and the co-operative movement was a combination international economic and social innovation, the economic policies of the Senate of the Grand-Duchy of Finland and the resources and connections of the country’s educated class.

On the initiative of Pellervo, the first Co-operative Societies Act was enacted in 1901, paving the way for a wide-spread co-operative movement. Co-operative credit societies, dairy co-operatives, and shops and central wholesale cooperatives were established as a joint effort by farmers, workers, and progressive educated classes. Co-operatives laid the foundation for a completely new business model and form of economic activity. Once set in motion, the wheels of development turned fast. The co-operative movement evolved into a significant economic power in the early decades of the 20th century.

Joining the movement

Paasikivi was a member of Pellervo from its early days until his death, from 1900 to 1956.Having earned his law degree, Paasikivi soon became a legal counsel for Pellervo and a secretary to the board for the period 1901–1903. He was the first salaried lawyer in Pellervo, and in this position he was one of the pioneers building the foundations of the movement in Finland. According to the annual report of Pellervo: “As soon as it was known that the Cooperative Societies Act would be passed, the board deemed it necessary to employ a competent legal counsel to take responsibility for any legal questions and to contribute to the preparation of the code of conduct and handbooks and inspect and validate the by-laws proposed by rural cooperative societies. For this position, the board has employed J.K. Paasikivi, Doctor of Laws.”

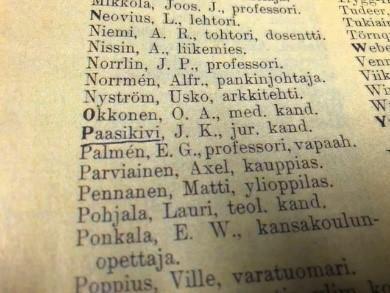

Paasikivi was a member of Pellervo from its early days. He first joined as an annual member in 1900 and became an ordinary member in 1912.

Through his roles in Pellervo, he had thoroughly embraced the social principles of the organisation. The movement was about an extensive social reform programme. Paasikivi wrote: “However, the significance of the co-operative movement is not limited to economics alone, it reaches far beyond that. The co-operative develops the moral qualities of its members and, above all, teaches them to foster and uphold a strong sense of community and solidarity. The principle of ‘all for one and one for all’ is demanding; but it is also elevating and ennobling.”

As legal counsel, his duties included establishing the Central Lending Fund of the Cooperative Credit Societies (OKO) and he also served in its administration. The idea of a central lending fund was laid down in the charter of Pellervo in 1899. The groundwork laid down by Professor Julian Serlachius was finalised by a working group, in which Paasikivi was a member. After several amendments that required legal expertise, visits to the Senate and share subscriptions, the central lending fund was finally established at a meeting in 1902, with Paasikivi taking the minutes. Paasikivi was appointed as a deputy member of the board of governors and eventually an ordinary member from 1914 to 1920, while he was serving as the Director of Kansallis-Osake-Pankki.

Paasikivi’s stint at Pellervo was relatively short, but his role as a champion of the co-operative movement, which began as legal counsel, did not end there. After leaving his position as legal counsel at Pellervo and joining the State Treasury, he became a member of the board of Pellervo from 1903 to 1909. For some of this period, he also served as a deputy chairman of the board.

Aiming for social reform

Paasikivi’s connections with circles interested in social innovation and the co-operative movement were forged in the 1890s. Paasikivi was impressed by the radical social programme of the conservative Fennomans, and he joined the Finnish Economic Society, which represented the historical school of economics: according to its tenets, the state had the duty to remedy social ills by means of economic interventions, social policy, and research. The historical school of economics was thus strongly critical of classical economics.

Alongside the enlightenment ideals of his youth, Paasikivi adopted a strongly economic perspective in his thinking. Educating the masses was not enough, and it was equally important to eliminate economic disadvantages. In Paasikivi’s own words: “Education without economic foundation only breeds discontent. Education must walk hand in hand with economic progress, because otherwise, in my understanding, it cannot make a difference”. In 1907, when Paasikivi had been elected to the Parliament, Paasikivi became the Chairman of the Agricultural Committee and a nationally influential opinion leader. He advocated policies that aimed at providing land and income to the landless population – “turning all tenant farmers into little capitalists”.

Hannes Gebhard (1864–1933) and his wife Hedvig (1867–1961) played a key role in the establishing and steering of Pellervo and the co-operative movement in Finland. Gebhard’s study of farmers’ cooperatives in other countries, dated in Bonn on 14 December 1898, became basic reading for the movement. The book was published in 1899 at an opportune moment, only shortly before the February Manifesto, which would shake the foundations of the Grand-Duchy administration, providing the basis for co-operative activities.

Gebhard and Paasikivi met in the 1890s at the Finnish Economic Society and the committee appointed by Governor-General N. I. Bobrikoff to deal with the issue of landless population and its subcommittees for land acquisition and landless population. Gebhard and Paasikivi were also neighbours at the housing company Oiva, at Nervanderinkatu 11. Oiva was built in 1910–1911 and it attracted a number of Finnish Party activist as residents. Illustrative of the friendship between the two men is that Paasikivi was at Gebhard’s request one of the pallbearers at Gebhard’s funeral in 1933.

Paasikivi had become familiar with the co-operative movement even before Pellervo, making him one of the very early supporters of the movement. The Finnish Party showed interest in co-operative models in the 1890s. Paasikivi’s master’s thesis and article in Valvojamagazine of 1898 examined the German credit unions initiated by Franz Hermann Schulze-Delitzsch. In the spirit of liberalism, this particular credit union model was designed to support urban livelihoods and industries. The prevailing co-operative model, which was based on the idea of Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen and which Gebhard advocated at the same time, focused more on social policy and on rural populations. Paasikivi did not challenge Gebhard’s thinking, although Finland did see a number of urban credit unions established in the model of Schulze-Delitzsche.

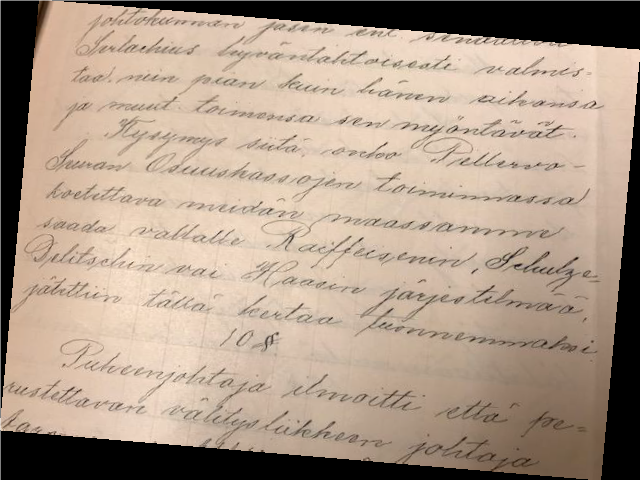

Pellervo Society’s board engaged in an ideological debate on the essence of the co-operative movement. Minutes of Pellervo Society, 7 September 1901. Eventually, the Raiffeisen model, which was better suited for an agrarian society, gained a foothold in Finland.

Ideals vs. reality

Paasikivi’s memoirs describe how the general economic thinking expanded during the 1910s from questions pertaining to social policy to involve wider economic phenomena. Owing to the critical political situation, social reforms were put on hold. The radical programme of the conservative Fennomans was not enough to win the support of working class and landless rural voters against the Social Democratic Party. Reformists were disappointed in the poor proletariat and the poor proletariat grew tired of waiting for reform. Scepticism towards liberalism was lifted and reservations against the economic role of the state grew stronger.

Paasikivi was among those whose thinking shifted from advocating social reforms towards more general economic thinking in the climate of the 1910s. His memoirs show how he never really lost the ideals of his youth. He saw that smallholder farming, in particular, provided a security of supply for Finland; farmers would serve as a pillar of industry and trade. The urban population and factory workers with adequate purchasing power would maintain healthy agricultural production. Paasikivi considered centralisation an unwelcome development: it would take decentralised social structures and economic actors of many different sizes as in this way “life will be richer and more varied”. Coming from a small business-owner background, he had a realistic and pragmatic approach to economics. There needed to be a balance, with earnings exceeding expenditure. Saving was always wise. Paasikivi wanted all sectors of society to engage in a “life of a modern, cultured person”.

Funding the movement

If the social ideals at the root of the co-operative movement would never really leave Paasikivi alone, neither did the development and financial needs of co-operative enterprises. At the State Treasury, Paasikivi channelled loans to dairy co-operatives and even to the Schulze-Delitzsche-style craftsmen’ credit society in Kurikka. Kansallis-Osake-Pankki, a Fennoman bank, also provided loans to fund expanding co-operatives which were regularly struggling to manage their growth. The role of the creditor was not easy. As Prime Minister in 1945, Paasikivi wrote in his diary, at a time of immense pressures due to the ongoing war-responsibility trials, that in spring 1918, he had granted an unsecured loan of 6 million markkas to Väinö Tanner, the Director of Elanto for the establishment of the Cooperative Wholesale Association (OTK). The next year he had saved Elanto by preventing Tanner from taking out a two-million-dollar loan. As a lender to Hankkija, the Central Agricultural Supply Co-operative Society, his moods varied “from deep concern to a great sense of relief”.

The national symbol of the co-operative movement

Much later, as the President of the Republic, Paasikivi carried a special symbolic significance for the co-operative movement. In this role, he shared the podium with another veteran of the co-operative movement, Hedvig Gebhard, who outlived her husband by several decades. Paasikivi wrote in his diary on 2 October 1949: “Pellervo’s 50th anniversary celebrations at the Fair Centre. A great event, although it lasted 3½ hours. Before the party, a delegation from Pellervo came to greet me and present me with a medal commemorating the 50th anniversary and the history of Pellervo and co-operative societies.” His image as a figurehead for the popular movement was made complete by his secondary role as a farmer from Kerava and as one of the leading members of Elanto co-operative.

Paasikivi’s influence has been felt by several generations since. Finland became one of the world’s most co-operative-oriented countries. The memorable words of the young legal counsel of Pellervo, written in 1902, express the legacy of the movement: “The Act as such cannot achieve anything. It only provides the external framework, within which life can happen. A piece of legislation can remain a dead letter. Or it can be of great import, provided that people are able and willing to use it, if people understand the meaning of the co-operative spirit and wish to abide by it.”

Sami Karhu, Lic. Phil., is the Managing Director of Pellervo Coop Center.

Sources

- Kari Inkinen, Mauno-Markus Karjalainen: Osuustoiminnan juurilla. Aatteen sankareita vai veijareita. Pellervo-Seura, 2012.

- Markku Kuisma, Annastiina Henttinen, Sami Karhu, Maritta Pohls: Kansan talous. Pellervo ja yhteisen yrittämisen idea 1899−1999. Kirjayhtymä, 1999.

- J. K. Paasikiven päiväkirjat 1944−1956 osa 2. WSOY, 1986.

- J. K. Paasikivi: New edition of Osuustoimintalain pääkohdat. Pellervon kirjasto no 10. Pellervo-Seura, 1902.

- Minutes of Pellervo Society, 1900–1908 Pellervo-Seura archives. Osuustoimintakeskus Pellervo ry.

- Tuomo Polvinen, Hannu Heikkilä, Hannu Immonen: J. K. Paasikivi: Valtiomiehen elämäntyö I, 1870–1918. WSOY, 1989.

- Tuomo Polvinen, Hannu Heikkilä, Hannu Immonen: J. K. Paasikivi: Valtiomiehen elämäntyö II, 1918−1939. WSOY, 1992.

- Suomen Osuustoimintalehti 1956.